Since Jan van Eyck painted a man with a serious glance and a scarlet headpiece in 1433, at the very least. Artists have made self-portraits, which are usually accepted to represent the artist himself. It’s possible that the same artist started a long-standing practice of including self-portraits into depictions of other subjects, historical or contemporary, as early as the next year.

Sometimes, a reflecting surface appears to display what should be the actual space that the spectator is occupying outside of the painting, leaving viewers perplexed. This is the result of these paintings.

Occasionally, they retroactively introduce themselves into occasions that transpired much earlier than the artist’s arrival. They occasionally depict the artist honoring the subject matter of the painting or drawing. The viewer’s attention to a particular feature of the scene being painted. Additionally, they may serve as cunning messages from the artist to the audience.

1. Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait (1434)

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait (1434)

The figures who enter the chamber where Giovanni di Nicolao di Arnolfini. An Italian trader in Bruges, stands with his wife (whose identity is unknown). Raising his hand in greeting, are among the most well-known examples of this occurrence.

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait (1434)

In the painting’s center is a convex mirror that displays two men. Additionally, one of them extends a friendly hand and dons a red chapero. A stylish turban-style cap, indicating that he is the same individual as the man donning the same attire in what is most certainly the 1433 self-portrait that popularized the genre.

2. Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi (1475)

Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi (1475)

Master Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli created this piece to adorn a chapel in Florence. It depicts a scenario from the Bible where three kings honor the baby Jesus. Painters loved to employ scenes like this one to showcase expensive materials and fashionable apparel. Gaspare di Zanobi del Lama, a prominent member of the Medici family with a blue robe, is depicted in the tableau, commissioning the work and gazing directly at the viewer. Other notable Medici family members are also featured.

Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi (1475)

Similarly making eye contact with us is the artist himself, standing at far right in a golden-brown cloak.

3. Raphael, School of Athens (1509–1511)

Raphael, The School of Athens (1509–11)

Artists honored the best personalities from that era during the Renaissance. Which turned to ancient culture for guidance. In Raphael’s fresco, a group of classical philosophers, mathematicians, physicists. The like have gathered, with Aristotle and Plato occupying the central positions. Characters like Zarathustra, Heraclitus, Archimedes, and Socrates are also present.

Raphael, The School of Athens (1509–11)

The artist himself, looking out at the viewer, stands next to multi-hyphenate mathematician-astronomer-geographer Ptolemy.

4. Quentin Matsys, The Money Changer and His Wife (1514)

Quentin Matsys, The Money Changer and His Wife (1514)

Matsys depicts a guy measuring gold pieces and jewels. While his wife reads a devotional book and leans in his direction. One could argue that the picture merely depicts a scene from a busy metropolis. Whose economy relied on workers like him. However, the artist seems to be reminding the audience that there are more important things than making money by including a picture of Christ and the Virgin Mary in the scenario. An overlooking Antwerp window can be seen in the foreground as the artist works on the painting. As well as a little convex mirror that places us in the same position as if we were standing outside the window and peering in.

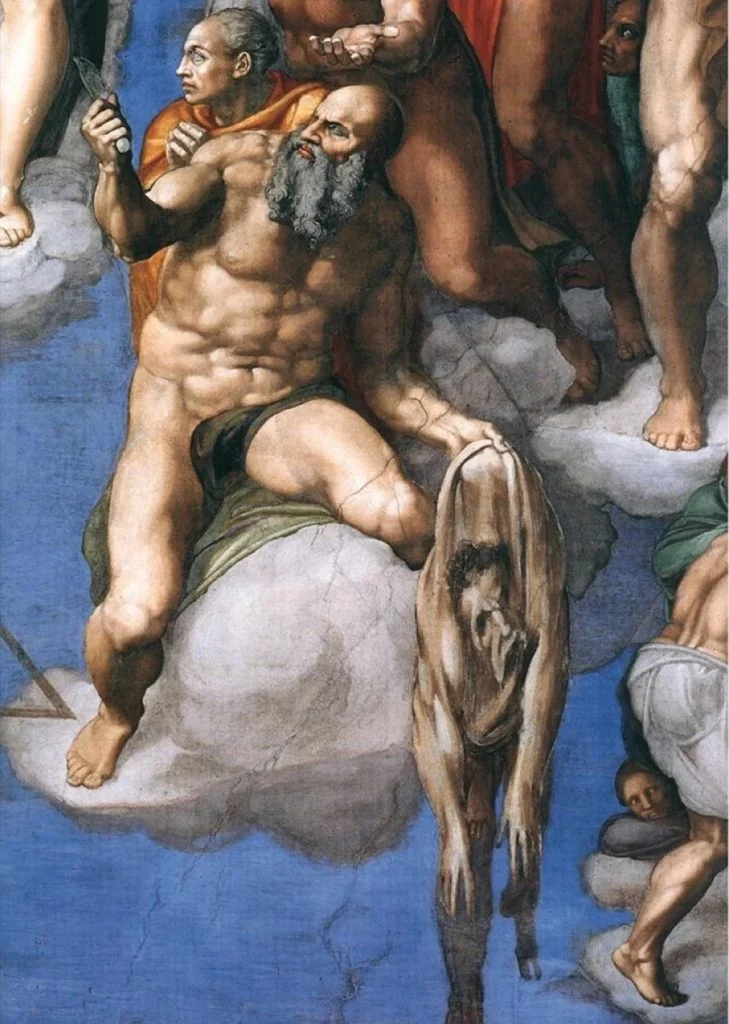

5. Michelangelo, The Last Judgment (1536–41)

Michelangelo, The Last Judgment (1536–41)

Between 1508 and 1512, when in his 30s, Renaissance artist Michelangelo began painting the Sistine Ceiling at Pope Julius II’s request. It was a challenging commission from the start, and he even expressed his displeasure in a sonnet from 1509: “My brush, above me all the time, dribbles paint so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!” Maybe a glutton for suffering, Michelangelo would return to the chapel to paint The Last Judgment over the altarpiece some twenty-five years later. He must have felt immense anguish, being around 67 years old when it was completed. Thankfully, he left us with a sign.

Saint Bartholomew holds his flayed skin as a symbol of his martyrdom. Cleverly substituting his own visage for the saint’s, Michelangelo seemed to be saying, “I’m dead lol.” In 1925, on the 450th anniversary of the master’s birth. Italian physician and author Francesco La Cava became the first to understand this and wrote a book about it.

6. Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath (1609–10)

Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath (1609–10)

A young shepherd named David, in the biblical story, killed the giant Goliath who was ten feet tall and had dared the Israelites to send someone to fight him, using a slingshot. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio painted the story with emotional complexity, substituting his own head for the giant’s in the process.

It’s possible that he painted in order to plead for his own life. The seasoned fighter had a reward on his head after killing a member of a powerful family not long before he painted this picture. Caravaggio might have sent the picture to a patron in an attempt to win their forgiveness.

Either way, he was going to die a few years later, without ever receiving forgiveness.

7. Clara Peeters, Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels (1615)

Clara Peeters, Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels (1615)

Still lifes dominated Dutch art from the 17th century, showcasing enticing food and beverages. Clara Peeters, an Antwerp-based painter, created this classic work in the genre; the Mauritshuis museum, its current owner, asserts that she was among the first to paint food still lifes.

In addition to food, it has expensive objects like a Chinese dish and a gilt Venetian glass.

Clara Peeters, Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels (1615)

Peeters inserted herself in two ways: first, she painted her name carved into the handle of the silver bridal knife, therefore “signing” it. The pewter earthenware jug reflects her face with a white cap on it, taking only a minute to notice this.

8. Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas (1656)

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas (1656). Collection of Museo del Prado, Madrid.

This enormous, ten-foot-tall canvas, widely regarded as one of the greatest works of European art (and undoubtedly one of the most contested), features Velázquez’s portrait of the five-year-old Infanta Margaret Theresa, daughter of King Philip IV of Spain, with her companions. The artist works with layers of illusion and reality, manipulating the relationship between the depicted space on the canvas and “real” space.

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas (1656). Collection of Museo del Prado, Madrid.

With paintbrush and palette in hand, Velázquez stands in the middle of the composition, working on a sizable canvas that is facing away from the observer. The mirror in the distance reflects the two persons half-length. They could be the king and queen, The observer or I see Velázquez working on the canvas with two figures in the same orientation.

What does Velázquez’s inclusion in such prestigious company signify? According to art historians, he was advocating for artists to be given more respect; at the time, there was a heated argument over whether painting belonged in the liberal arts or was only a mechanical skill, and this would have required a definite stance.

9. Jacques-Louis David, The Coronation of the Emperor Napoleon I (1806–07)

Jacques-Louis David, The Coronation of the Emperor Napoleon I (1806-07)

In front of 20,000 spectators, Napoleon Bonaparte proclaimed himself Emperor of much of continental Europe in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. Pope Pius VII was among a group of the most esteemed foreign dignitaries, which also included ambassadors, ministers, and royals. Napoleon was supposed to receive the crown from the Pope, but in a display of audacious self-regard, the commander grabbed it and crowned himself. Thus, in spite of the title of the artwork, it depicts him coronating Empress Josephine.

Jacques-Louis David, The Coronation of the Emperor Napoleon I (1806-07)

We catch a glimpse of the artist in the act of sketching the scene from a hidden balcony. The 33-foot-wide painting caused such a stir that its creator, Louis Léopold Boilly, painted the people viewing the piece at the Louvre, where it is currently kept.

10. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Au Moulin Rouge (1892–95)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Au Moulin Rouge (1892–95)

During the Belle Époque, the interlude between the Franco-Prussian War and World War I, the renowned nightclub Moulin Rouge, also known as “the Red Mill,” flourished. The club got its name from the notable red windmill located on its roof. Visitors, laborers, businesspeople, and artists flocked to the posh Montmartre neighborhood to witness groundbreaking performances, some of which were scandalous, as well as scenes like the can-can dance, which originated at this location. Famous club posters were designed by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who is seen here as the small figure in the background with his cousin, doctor Gabriel Tapié de Céleyran.